A working essay that considers the theories of Judith Butler and Neil Evernden as a step forward from social distancing to one of the care for others.

My walks in Seattle this spring have taken a different character to previous years of urban exploration. How people and spaces in the city relate to my body has become a prominent examination and negotiation in my everyday. The social formation of the city is no longer a subconscious or overlooked part of the mundane but an active mental and physical state. The writings of Neil Evernden and Judith Butler have become constant companions with me in the city as I examine this adjusted life. Both ask us to question our relationship to others and frame space in terms of care. This critical idea - care - will be instrumental as we reduce our social distance and reconnect within space(s) to begin to make a path forward.

During years of walking I found that my eyes tended to follow two distinct patterns. First, an expansive seeking field scanning up and around, side to side, and toward the horizon. A constant view into the urban fabric to comprehend patterns, form, and social production. The architect and geographer in me geeking out on a derive, so to speak. My second view was a very inward and downward view. Head slightly tilted down and focused within my next step and often fully contained within my body. Quite an introspective gaze. This posture was likely a result of years of walking in a slight pacific northwest drizzle. A slight tip of my head downward to keep my glasses just inside the edge of my gore-tex hood or slightly covered by the top of my head and thus relatively clear. Given our current mandated six foot social distance, I find myself committed to a shifted view. A view that looks into a middle distance and my immediate future space. As I navigate this new regulated everyday I continually and very consciously take up Evernden’s questions regarding field of self:

Where do we draw the line between one creature and another?

Where does one stop and the other begin?

These questions are at the heart of The Natural Alien: Humankind and Environment, written in 1993. Neil elaborates these questions in an effort to understand and consider our bodies as more than defined by our skin, physical boundaries, or as clearly defined objects. We are defined as fields of self and fields of care.

What all this suggests is that our assumptions of separateness are unacceptably simplistic, and that we might more closely approximate the facts of our existence by regarding ourselves less as objects than as sets of relationships, or as processes in time rather than as static forms.

Neil uses schools of stickleback fish as example of how organisms define territory beyond a particular body. Phantom limbs as example of how our mental and physical definitions of self are not always aligned. And how, through the act of naming, our understanding of self is culturally defined and intrinsically linked to how our parents, a key other, are defined. These are quite complex phenomena which he explores in depth. For this essay, in short, field of self is as if the boundary of what is to be considered self has expanded to the dimensions of territory, mental image, or a socially defined relationship. We understand and project ourselves as being the size of the territory no longer an organism bounded by skin but an ‘organism-plus-environment’ revealed as a gradient of action. This ‘organism-plus-environment’ definition is supported by an understanding that the ‘true’ version of ourselves is that of the phenomenal body. Inverting the typical definition of self as object and within the theories of phenomenology to understand two important points. “One is that the phenomenal body is the one we live by; the other that the objective body exists only conceptually.” This directly questions that cultural idea that the “objective as real.”

My current socially distant walks along with a walk by Judith Butler in San Fransisco are helpful in navigating this theory of self and point to necessary steps needed to move forward together in a supportive and resilient way defined by care.

My field of self at the moment is strongly defined by three ways to navigate my relationship with others. The first is my physical body position and continual need to maintain a six foot distance between myself and others. At the scale and frame of reference of the body this is a very direct definition and spatial response. I can readily measure this distance with the span of my arms or my pace. There is a tangible aspect to this required social distance. I see someone coming about 1/2 a block away within my new middle distance focal length. I attempt to make eye contact and then begin to scan the area to find a route to pass. Typically this takes me past the curb and slightly into the street. As we approach we both shift to maintain distance. I say hello. I then move back onto the sidewalk and continue on my way. This 30 foot sequence is now very much a conscious calibration of my field of self. To care for my body and health I understand my field of self quite literally as a constantly shifting six foot radial zone. At the moment, a social understanding is being established in the city as to how far the effect of my body extents beyond my skin. A mutually understood relationship between various fields of self.

This gained knowledge and social formation generates the following question - What is the level of care I owe others and myself while in public? This everyday definition building is just starting to be honed and is producing new expectations of what constitutes self. This shift in social definitions is sustainable at the moment and very much accepted. As more people come together and regulations shift we will be asked to produce a new set of answers. At the moment we are able to project our field of self digitally and during the times when we get closer we shift to a set of specific body avoidance tactics. If distance is not able to be maintained we then establish tight barriers. We are digitally expanding our field of self vastly outward while simultaneously retracting and confining our near body/skin field of self definition when touch is a potential.

Retreat

On my walks I have come to understand this adjustment and how it clearly relates to others. We are socially producing a pedestrian relationship that is a form of adaptive ‘managed retreat.’ The strategy of ‘managed retreat’ at the urban and regional scale is a lively discussion to develop a response to climate change and sea level rise in particular. Generally, this strategy is available to any system or relationship given the presence of a new and immediate feedback loop. A clear response to an approaching un-known or known risk. The key mechanism is an increased distance from the other. As with sea level rise, the current distance needed to maintain a sustainable relationship in society is not a random distance but one directly defined by my field of self and field of care. My field of self in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic is defined by the phenomenon of my breath as projected beyond my body into the air and remaining on various surfaces a given time after my physical body has left the scene. This phenomenon is not limited to my casual walks down the sidewalk. A ‘return to work’ and more common close engagement with others will only focus more attention on the overlap of our fields of self and our impact on the health of others.

If we were to regard ourselves as a ‘field of care’ rather than as discrete objects in a neutral environment, our understanding of our relationship to the world might be fundamentally transformed.

This transformation is two fold. First is the acceptance of the fact that the environment is no longer neutral. This question has a long history in modern western theory. A critical theory lens requires us to acknowledge we inhabit and uneven environment one which is not a neutral abstract construct, empty, or ‘tabla rasa’. Second, we are confronted with a reality in which our care for others, and their care for us extends well beyond our discreet bodies. Current healthcare recommendations to reduce the spread of infection regulate a continual movement of my body away from others. The clarity achieved by this polity at the moment is because it is framed by the fact that my relationship to others is defined as a threat not just difference.

What is possible when we transform our relationship to others away from risk, difference, and self toward care? The dialectic relationship Evernden is talking about between self and care is a needed critical shift in meaning. Much of the discussion on ‘managed retreat’ is centered around a response to an approaching threat. This linear understanding misses the point. As I walk toward someone on the streets of Seattle I have come to realize that it is not they, them, or the other that is a threat to my field of self but I am also a threat to them and in being a threat to the them I become a threat to myself. Our respective fields of care intersect and become relational and in interest of each other. Our fields of care become mutually defined. I am not able to negate the health of others because in doing so I negate the health of myself. A productive framework is established. One not governed by a ‘managed retreat’ or drive to define myself through distance and separation but toward a ‘managed approach’ where I am defined by how I approach (care for) others and thus myself.

Approach

One can argue - wait we are already in the deep end and we must retreat. How a person is situated is a critical frame of reference and where we all begin. However, we must hold the relational definition of fields tightly at hand and recognize that it is not tenable to conceive of a neutral space that allows a singular retreat from the edge or others. We must transform our thinking to include the fact that as we retreat from one we perpetually approach an other. Every retreat is defined by another approach. We must resist the concept of a dual frame in a neutral landscape but one of mutually defined relationships defined by approach. If we manage a retreat from the edge, or someone, we also need to focus on the care for where we are headed and who we are approaching?

Before jumping fully on board with this theory of a field of care defined by perpetual approach we need to consider the strategy commonly used as scales shifts and contact is imminent.

As I walk the city, separation is a clear strategy being employed as people return and become more active. Our retreat found ultimately not sustainable and we must navigate an approach. The ‘new normal’ now being considered. At the moment we are able to stage a series of encounters defined by clear moments of approach, distance, and return to ‘managed retreat.’ When this becomes too dynamic, and socially distant relationships can not hold, we tend to fix the conditions and space. In the everyday this is experienced while in line at various stores, food banks, and shelters. We see lines set at 6-foot intervals. This spatial fix comes to define our relationship with others. To access a service, nourishment, or other social interaction the moment clear healthy movement and retreat cannot be maintained a momentary fixed condition is established. Fixed conditions are problematic and to ‘managed retreat’ they cannot be maintained in systems and human environments. Ultimately systems and space fail when they become fixed and static. Just as the built environment is not neutral and friction-less it also cannot sustain social production if it ceases and becomes fixed.

How do we approach this problematic social and spatial fix? A third strategy is typically employed to answer this question within our working definition of field of self. The first part of my exploration has been defined by movement. A move to shift orientation, relationship, and position as the principle strategy. As our movement becomes limited we constrain and fix space relationships. To release this untenable fixed condition we build barriers as a third strategy. In this case, a mask, gloves or other various forms of personal protective equipment (PPE). To care for ourselves (and others) we constrain our field of self to points very close to our skin/body definition. Thus, if movement and fixed positions are not options I wear a mask. I build a boundary to keep my self contained. Not the body contained within my skin but a barrier to contain my breath and fluids. It is this projection of my breathing and fluids beyond my body that the state currently defines as my field of self. The corollary to this in the built environment is the act of building a wall. This can also be seen as an analog to the urban question above regarding how to address climate change and sea level rise. If a managed retreat is not taken and we want to continue to be in contact with the edge at a geographic and urban scale we rely on structured barrier. We design an edge of tightly restricted interface.

The moment will come when our cities, spaces, and bodies are to the point where the now available retreat, temporary fixed positions, or a direct barrier will not sustain a way forward. One may question if they ever were able to.

What happens when we make our current moment not about retreat, barriers or static bodies but a perpetual approach defined as a field of care? This shift in logic or fundamental transformation as articulated by Evernden asks us to acknowledge that there is no moment where I am not approaching them, they, or the other. And simultaneously this means there is no moment where I am not approaching me, myself, and I. How I approach others and the world is a direct response to how I approach myself. My care for others is inherently care for myself. Care as:

an instance of mutualism in which the fates of two beings are so intertwined as to make them almost indistinguishable. Is a plant a plant, or a co-operative system of formerly independent creatures?

Mutualism results in an adaptive perspective. I am not tied to a particular strategy to respond to others. As I approach, I place myself in a position to understand who and what is approaching. To approach becomes an act of working to understand - What is my field of care? How does my field support the care of others and thus myself? From this situated knowledge I can then approach.

As we work to navigate fields of self we are also presented clearly with the body as the site of identity and value. Judith Butler is instructive in her Senses of the Subject (2015) and elaboration of the body as critical to understanding self, being, and the built environment.

Ultimately we must invest ourselves in the world. And in many instances this investment is so profound as to make any distinction between the visible body and the loved other ultimately trivial. Far from a simple case of spillage, this is clearly the inevitable mode of development for sentient beings. Whether we refer to it as attachment to the other or as extension of the boundaries of self, the fundamental fact of our existence is our involvement with the world.

Her ideas build upon this field of care framework to approach our questions of how we are mutually defined within others. She situates us not in a reactive mode where we perpetually adjust through retreat, fix, or barriers to our field of self (both physically and conceptually) but an active stance where we approach through care the world around us as we live.

So if we are to speak about desiring to live, it would seem in the first instance to be emphatically a personal desire, one that pertains to my life or to yours. It will turn out, however, that to live means to participate in life, and life itself will be a term that equates between the ‘me’ and the ‘you,’ taking up both of us in the sweep and dispersion.

To shift our approach to others and to life as one which does not “pertain to my life or to yours. It turns out that to live means to participate in life itself as a term that equates the me and the you.”

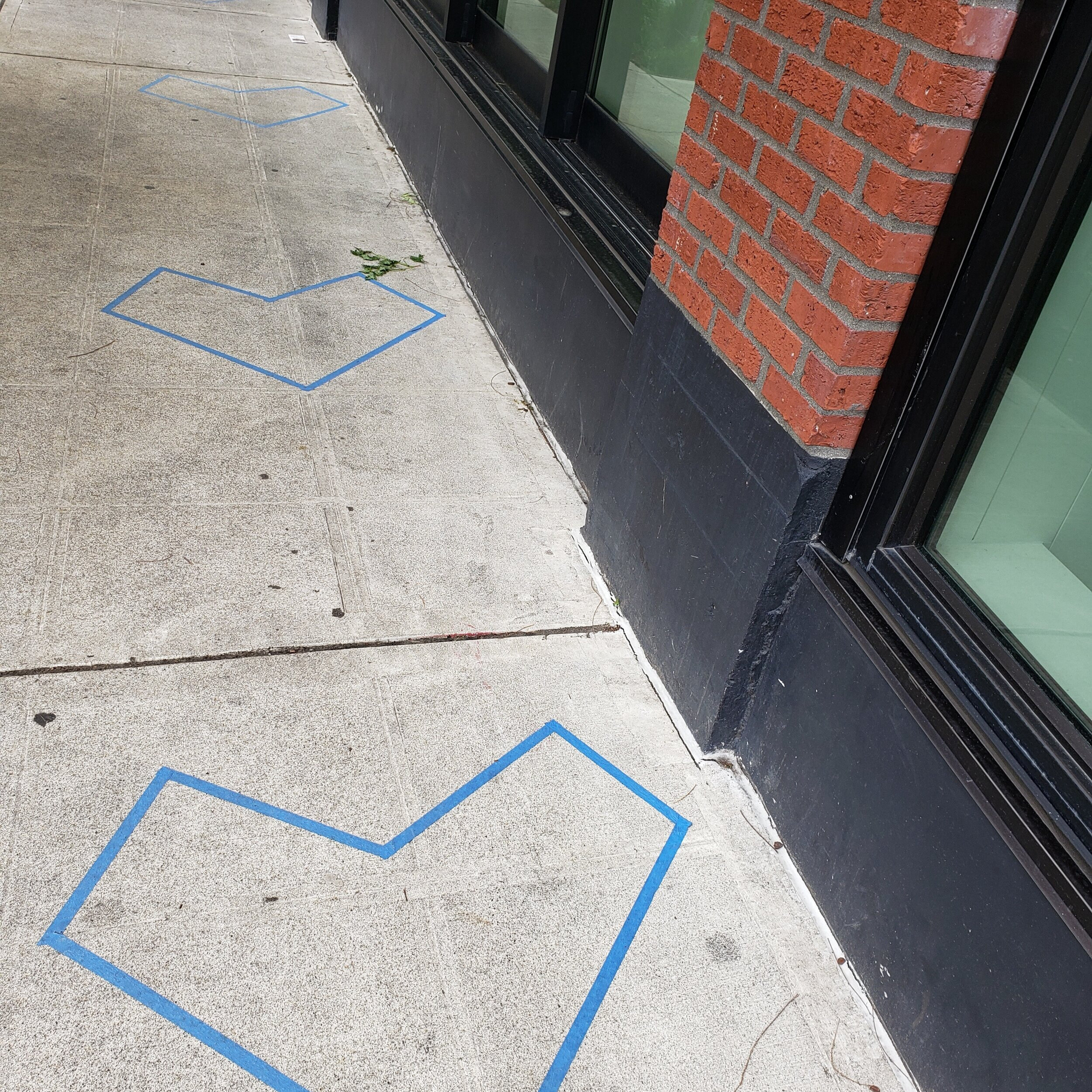

She puts forward a sharper critical definition of mutualism as one where “I cannot secure my needs without securing the other’s.” This critical definition is spatialized at the moment as literal marks on the ground. Again, we return to the moment when I stand in line to purchase my food and secure my various needs. I approach a regulated field of care represented clearly by lines on the sidewalk. These minimal lines are just the most recent addition to our urban environment to aid in our navigation of a mutual definition of self.

We hear talk of a ‘new normal’ into which we will somehow emerge. However, this is not a condition of emergence but an act of making. We are currently making a ‘new normal.’ Butler and Evernden compel us to remember that “we see in nature what we have been taught to look for, we feel we have been prepared to feel… Reality is transformed by what we are prepared to perceive.” To have agency in the production of any ‘new normal’ we must prepare to ourselves to see the world as a means to approach others with care. Critically we need to make a world not defined by perpetual retreat, fixed relationships, or barriers.

The production of space through acts of approach and a focus on a field of care are present in our everyday. It is just that on most days we do not see the mundane flow of our everyday as a critical act of making a field of self and care. Butler illustrates these critical acts on a walk with Sunaura Taylor in the Examined Life Series.

To choose life in our ‘new normal’ is a recognition that we need to approach others as from a field of care. To live and to sustain myself is an act of sustaining others through care. Our ‘new normal’ is to care for others and thus ourselves through everyday acts and the production of space embodied by a new ethic. Butler frames a next step forward:

It would be an ethic that not only avows the desire to live, but recognizes that desiring life means desiring life for you, a desire that entails producing the political conditions for life that will allow for regenerative alliances that have no final form, in which the body, and bodies, in their precariousness and their promise, indeed, even in what might be called their ethics, incite one another to live.

I continue to walk…